IPHD Food for Education Programs Supported by USDA

Since IPHD began its school lunch program in 2001 under the USDA McGovern-Dole Food for Education Program, IPHD has distributed 119,868 metric tons of U.S. food, and over 4,100 metric tons of locally purchased or locally contributed foods.

IPHD provided American food commodities donated by USDA annually to almost 500,000 primary and pre-primary or kindergarten children in prepared meals daily between 2001 and 2008, and between 2008-2011 to over 200,000 children daily. Over this 10-year period, IPHD fed a total of 3,199,285 children. From 2001 through its current programs IPHD’s efforts will have realized a total value of $186,855,043

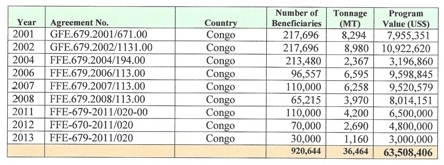

Congo Republic (a program in transition to local funding)

In the Congo Republic, IPHD fed annually between 217,696 to 65, 215 children, including pygmy children in Lekoumou Province.

In 2010-11, IPHD along with the Ministry of Education developed a plan whereby IPHD will transition the Food for Education Program to the Ministry of Education. As a result, USDA approved IPHD and the Ministry’s plan and will provide U.S. food commodities and cash on a decreasing annual basis between 2011/12 and 2012/13 school years, after which the program will continue with annual budget allotments by the Congolese Government. In 2011, the Congolese Government provided IPHD with US $4.7 million to be used for local food purchases and the improvement of school infrastructure. With local government funding, IPHD will reach another 30,000 children in primary schools, increasing the total to 140,000 children receiving school lunches daily.

Between 2001 and 2010, IPHD established 261 parent/teacher associations, with 2,496 members, distributed school supplies to over 50,000 children, and repaired 90 schools. Kitchens were created in all schools to allow for the preparation of the daily lunch. In addition, over 100,000 mosquito nets were distributed and 88,000 teachers and students received instruction on malaria prevention. As a result, absenteeism for malaria fell from 15.1 percent to 3.8 percent. Vitamins and zinc tablets were distributed to over 100,000 children. Over 30 schools received access to clean water through cistern construction. Enrolment increased from 45 percent to 52 percent, and dropouts fell to under 5 percent. School gardens were also created in 25 percent of the schools.

Testimonials:

* A girl student – “When I was in school last year, I was very skinny and could not attend class every day. This year, because of the school lunch, I am gaining weight and do not miss class anymore.”

* School Director – “Before the canteen when school children were informed that the next day was off, they were full of joy, jumped and sang a song that said “Lelo tokokota te”, meaning no class tomorrow, no class tomorrow”. Now when they are informed that the following is not a school day, they become sad and don’t sing any more, instead they shout “Faunio, faunio” meaning porridge, porridge.”

* A Parent – “Before the canteen started, my children’s performance at school was poor, and they did not like going. Since the canteen has started, I noticed that they read more and their test scores are better.”

* A Parent – “I wanted to send my son to Mama School. My son asked me if Mama School had a canteen. When I replied no, he cried and cried and refused to be enrolled in that school.”

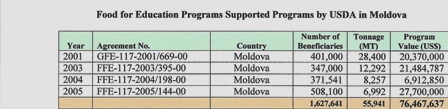

Moldova (a Program transitioned to the Moldovan Government in 2009)

IPHD began its Food for Education program in Moldova in 2001 and reached 401,000 pre-school and primary school children with daily prepared meals under this first agreement. Prior to 2001, the school lunch program was basically a milk program, which had disappeared with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990. In this first program, IPHD had to organize the vast infrastructure needed to reach almost 4,000 schools; this was one of USDA’s largest Food for Education programs. Local officials were often sceptical that IPHD would have success. The program put a good deal of effort into creating and strengthening PTAs and local community groups in order to develop the program infrastructure needed to effectively reach the large number of beneficiaries. As a result of IPHD’s success there were three other USDA/FFE agreements, 2003, 2004 and 2005. When IPHD began the program, there was almost zero funding for school lunches. When IPHD closed this program in 2008, the Moldovan Government was budgeting approximately $20-$30 million annually. Local community participation was the key to the success of this program. In 2008, IPHD transitioned 370,000 children in its program to Moldovan government support.

Under the four agreements with the U.S. Government IPHD had to repair and furnish school kitchens. Most were in terrible condition after years of disuse and neglect. By 2008, IPHD had developed and strengthened close to 1,500 PTAs and community groups. It also built water systems and sanitary facilities for a number of schools.

With bread flour provided from the USDA, IPHD made about 20,000 tons of pasta under these four agreements. Other food provided by USDA included potato flakes, rice, pinto beans, vegetable oil and in one year corn-soy-milk (CSM). During the period 2001-2008, 1.6 million children were fed, an average of 406,910 children per agreement annually.

In 2005, Dr. William Pruzensky, IPHD President, met with the Vice Prime Minister of Moldova who told Dr. Pruzensky that when IPHD initiated the program, he did not think they would succeed in its goal. He admitted he was wrong and said that IPHD had created such a vast community network that if IPHD were to leave or end the FFE program, the government would be forced to take it on and continue it.

IPHD saw this partly as a program to help build a more democratic society, and it made a greater and more lasting contribution to this end than most aid programs.

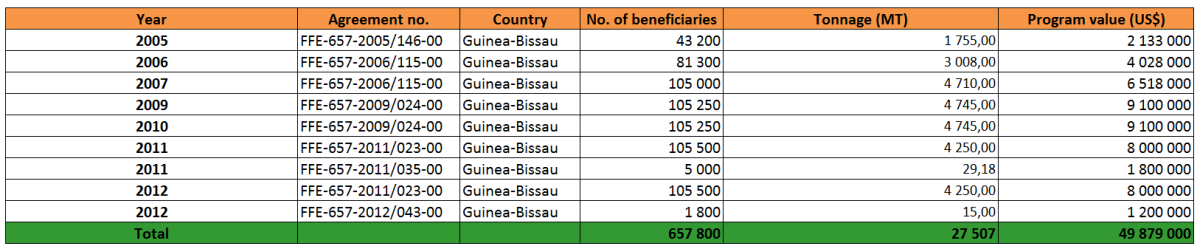

IPHD began its USDA-supported Food for Education Program in 2005 in this very poor country, listed as among the ten poorest nations in the world by UN statistics.

The program targeted 43,200 pre-school and primary school children in its inception; today it reaches 105,500 children daily in 400 primary or elementary schools and 60 pre-schools with meals prepared from USDA donated rice, potato flakes, beans, and vegetable oil, as also local foods. The program is concentrated in the central and western regions of the country. Every year final enrolment has increased over initial enrolment by 7.07 percent to 9.7 percent. The drop-out rate of those enrolled has fallen to well under 10 percent. Absenteeism has fallen from an average of over 2,000 children per month to as low as 1,160 children per month.

In order to undertake an effective FFE Program in Guinea-Bissau, IPHD enlisted the support of local communities to prepare and serve the food, to contribute with fuel and locally grown foods, and when possible with money. As a result, each school has a school lunch management committee. In addition, IPHD developed 270 local PTA groups, and in December 2010, along with AMIC (Associação dos Amigos da Criança), its local NGO partner, established the country’s first national PTA association, with the secretariat temporarily in the IPHD offices.

IPHD has also repaired, built and furnished school kitchens and built water and sanitary facilities for schools. Since early 2009, IPHD has also helped to create over 120 school gardens. While IPHD has strong support for its program, the government budget is small so IPHD is strengthening the private sector involvement to try to facilitate an eventual transition.

The 035 and 043 agreements were for pilots/studies on using a micronutrient product as a morning and daily snack